ime when Americans face each new day with trepidation as the country's laws and freedoms come under attack, the documentary "Water for Life" stands as an example of how values can triumph. The road isn't easy, and there are setbacks along the way, but that's part of the journey.

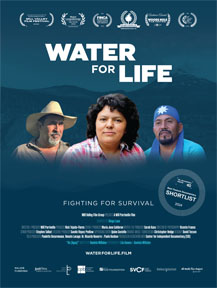

Director Will Parrinello, who has made Indigenous rights and the environment key subjects in his thirty-five-year career, delivers a film (available to stream on PBS) demonstrating the conflict between power, money, and influence against an ethos that considers people over profits and respect for the earth over exploitative usage. Three individual narratives of Latin American defenders of the environment share the common bond of respect for the spirituality of nature, and what it gives back to those who understand the connection between all living things.

What will people who follow this path do to protect the sanctity of their land and its resources?

Alberto Curamil is the Chief of the Mapuche people, who comprise 84 percent of the indigenous population in Chile. His great-grandfather fought to keep white men from crossing the Malleco River when the Spanish first invaded the territory. The Mapuche have been on the land for thousands of years.

When referencing his ancestors' past and how their land was stolen, Curamil said, "Now it's the corporations." The target is water resources, specifically the Cautin River, which Curamil calls "the lifeblood of our territory. It contains a spiritual force." It's all about building hydroelectric projects, thousands of them. The effort began in 2010 with construction slated for the "heart of ancestral lands".

Ma'ximo Pacheco, the former Chilean energy minister, believed that resources were "abundant" and could facilitate renewable energy. Manuela Royo, Curamil's lawyer, clarified the problem. "Several hydroelectric projects were approved without any consideration of them being in Indigenous territory." The constitution of Chile does not include a recognition of "the existence of Indigenous People".

The (UN) ILO Convention 169 outlines that in advance of any action taking place on indigenous land, the people "must be consulted". As Parrinello clarified when we spoke, "ILO Convention 169 on Indigenous and Tribal Peoples' rights was developed in collaboration with the United Nations, paving the way for the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP). The ILO and UN work together to protect and promote the rights of Indigenous and Tribal peoples, with Convention 169 providing a legally binding framework. The United Nations plays an important role in supporting 169's implementation while promoting broader awareness of Indigenous rights. However, UNDRIP is a declaration, while Convention 169 is a binding international treaty for those countries that signed it."

The government of Chile released a report qualifying the area as being without indigenous people. Journalist Ana Rodriguez is on hand to challenge that determination. Drawing such a conclusion would require extensive fieldwork, costing significant money and time. That in itself would serve as an impediment to moving forward with extraction.

In 1973, Augusto Pinochet took power in an American-supported military coup, ousting the democratically elected President, Salvador Allende. Pinochet's seventeen-year dictatorship escalated problems for the Mapuche. The government privatized the country's natural resources, gave land to the timber industry, and even traded water rights on stock exchanges.

A dilemma arises for the Mapuche as drought sets in, resulting in water shortages. If there is no "legal" right to the water that traverses their lands, usage can result in court cases claiming theft.

When Curamil goes to Santiago to speak about these concerns, he self-identifies not as an environmentalist but as a Mapuche Chief defending his land. Mauela Royo, Curamil's lawyer, asserts that the government's environmental report was deliberately falsified when they claimed that the project would have "no impact".

In July 2014, Curamil and his legal team take on the Chilean government. It is about a larger cause than the concern of the water itself. It is an element of a larger confrontation, which is to reclaim ancestral territories.

Anger and frustration lead to acts of violence. Timber trucks are set on fire, along with other incidents of sabotage against the forestry companies. Like any other movement, the anti-mining ranks aren't monolithic. In response to accusations of terrorism, Curamil responds, "Our life is at stake." His wife delineates, "Neither jail nor death can stop the struggle."

Two years after starting the legal case, Curamil has his day in Chile's Supreme Court (2016). They hand down a 4-to-1 decision in favor of Curamil. The Dona Alicia hydroelectric project is canceled, as are all other plans for the Cautï ? ? €™n River. The success is overshadowed as the powers that be see Curamil as a threat to future potential proposals. Curamil is ensnared by trumped-up charges of robbery in 2018, along with two other men. Despite no evidence, he is sent to jail. His young daughter, Belen Curamil, steps up to take his place while he serves eighteen months-- waiting for his case to be heard. In 2019, a court of appeals in Temuco acquitted him of all charges. It's clear that his activism was on trial-- and that his time spent incarcerated was as a political prisoner.

* * * *

(Note: You can view every article as one long page if you sign up as an Advocate Member, or higher).